Jails Continue to Hold in the Neighborhood of Their Capacity Quizlet

Michigan Enacts Landmark Jail Reforms

Historic legislation aims to reduce incarcerated populations, improve public safety

Overview

On Jan. 4, 2021, Michigan lawmakers adopted a package of 20 jail reform bills—a historic slate of changes affecting every aspect of local criminal justice systems. The laws, which took effect in 2021, are a model for state-level policy change affecting local jail populations and will protect public safety while helping thousands of people in Michigan avoid arrest and incarceration for low-level offenses.

The bills stemmed from the recommendations of the Michigan Joint Task Force on Jail and Pretrial Incarceration, a bipartisan group of state and county practitioners, policymakers, and people directly affected by the justice system, that the governor established to elevate jail reform as a shared priority. The group's task was to analyze data, statutes, and existing practice in Michigan and to recommend policy changes that could safely reduce jail populations. Legislators on both sides of the aisle, prosecutors, law enforcement officials, district court judges, and a diverse coalition of advocacy groups supported the task force's recommendations.

The resulting reforms eliminate driver's license suspension as a penalty for infractions unrelated to dangerous driving, increase the use of interventions in lieu of arrest, improve probation practices, and reduce the use of jail time as punishment for many nonviolent offenses. These actions will help keep families and communities intact, make better use of taxpayer dollars, and provide a template for other states to address the financial and human costs associated with incarceration in jail.

Background

Jails in Michigan are operated by the counties, and as a result, before 2019, state legislators did not typically view them as a priority. However, state-level policy plays an important role in the number of people sent to jail and the length of time they stay there, as well as in ensuring that people are treated fairly and equitably regardless of the jurisdiction.

It was in this context that the work of the task force began. The group started with a series of questions that no one at the state level was able to fully answer: Who was coming to jail? What were they coming to jail for? And how long were they staying?

Task force findings

To answer those questions, the task force examined 10 years of statewide arrest and court data and three years of data from a diverse sample of 20 county jails,1 conducted dozens of stakeholder interviews and roundtables, heard testimony from hundreds of people across the state, and reviewed relevant legal and policy research. The Pew Charitable Trusts and the Crime and Justice Institute provided technical assistance, including research and analysis, to the task force. Unless otherwise noted, the data in this brief was drawn from the task force's final report.2

Population growth

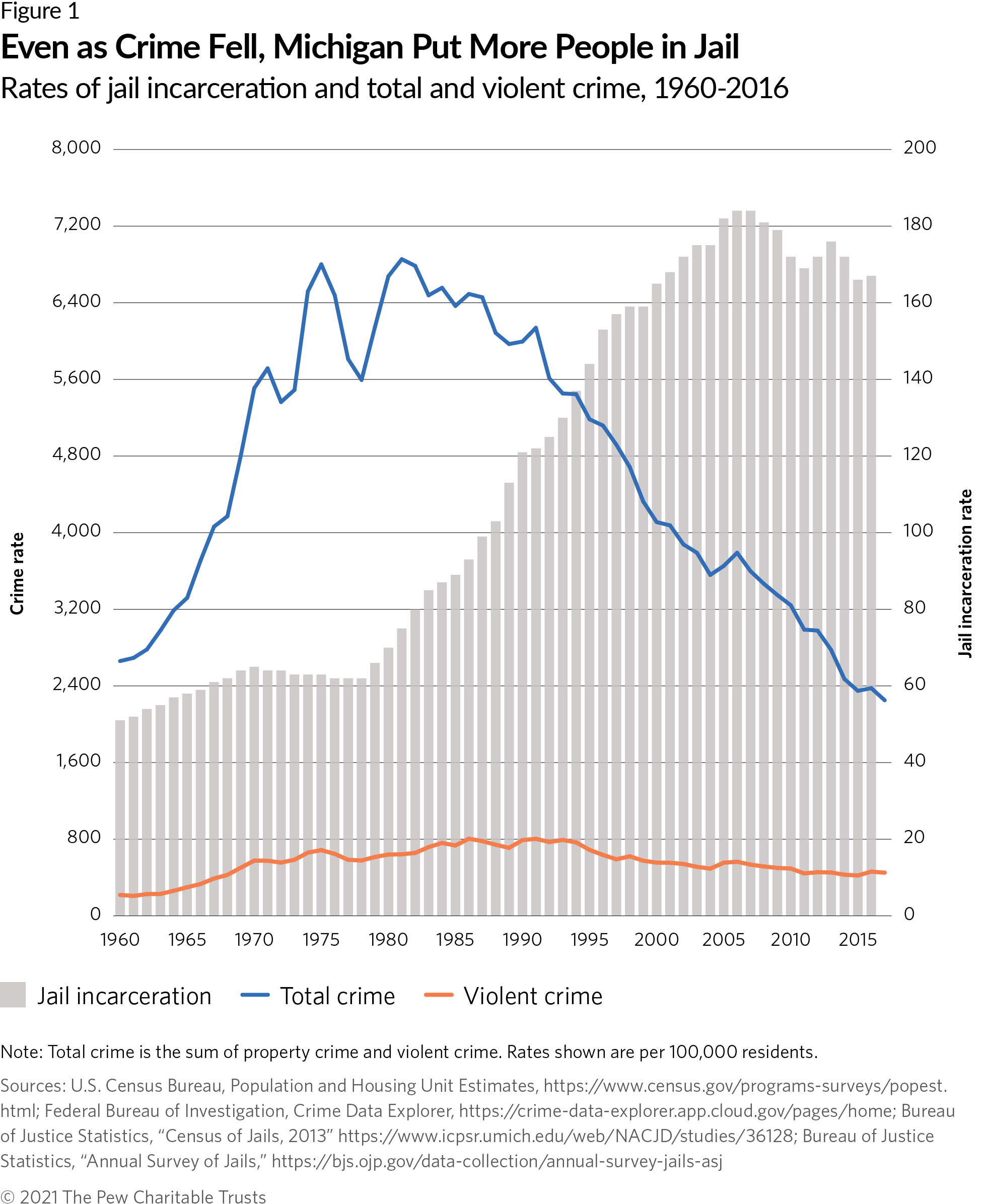

The task force found that Michigan's jail incarceration rate tripled from 1960 to 2016, even as crime in the state dropped to a 50-year low. (See Figure 1.)

Racial disparities

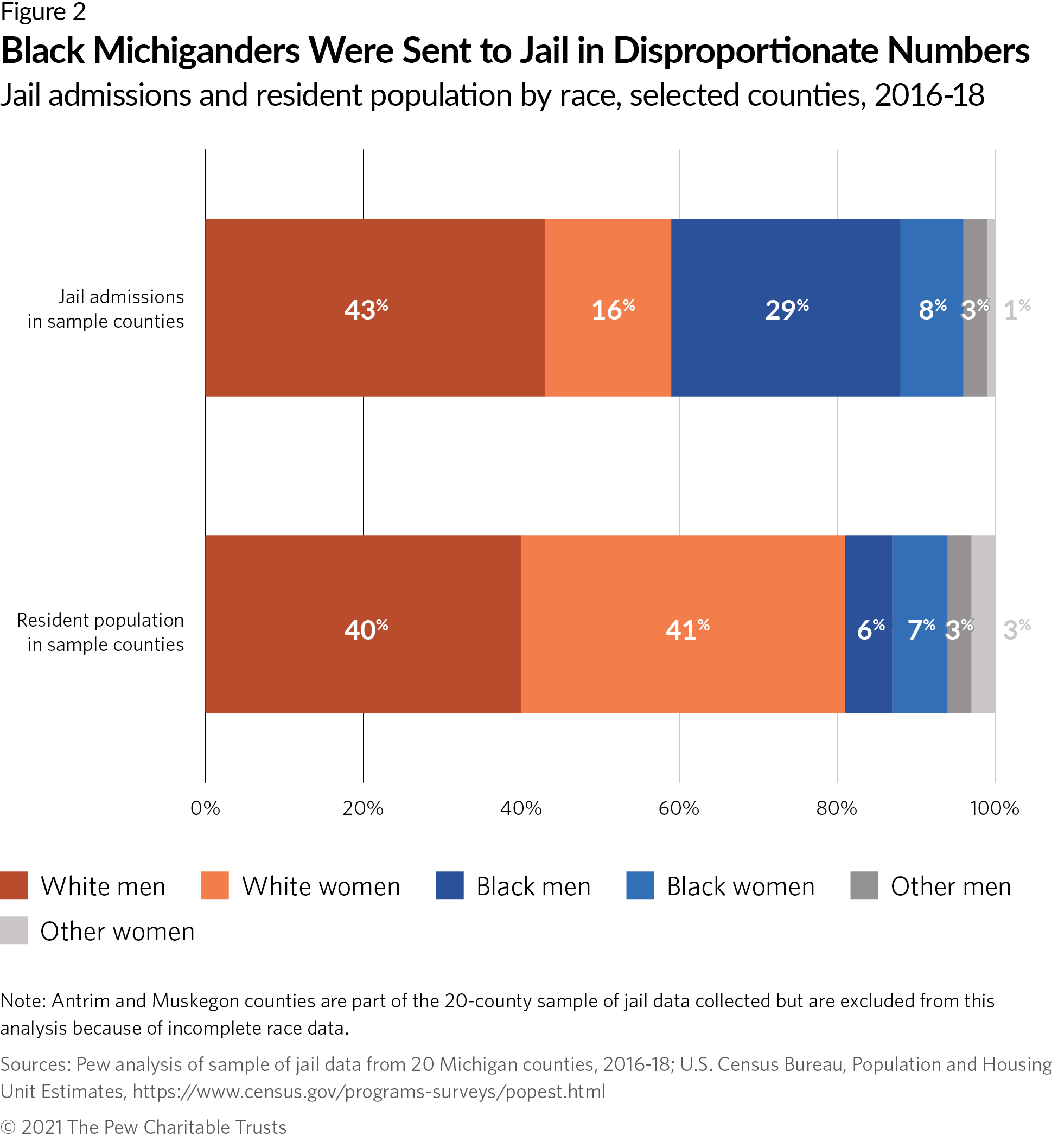

Black residents made up a disproportionate share of that jail population. For example, between 2016 and 2018, Black men and women were approximately 13% of the population in the counties studied but 37% of jail admissions. (See Figure 2.)

Many people held in Michigan jails were awaiting trial or serving sentences for low-level offenses, such as driving without a valid license or possession of a controlled substance, that pose little public safety threat. Yet some of them stayed in jail a month or longer, consuming space and other scarce resources.

Housing people in jails cost Michigan counties nearly half a billion dollars each year, and negatively affected communities throughout the state. Recent research shows that even short stays in jail have a destabilizing effect, costing people their jobs, housing, and custody of their children, and leading to other impacts that upend lives and increase the risk of future reoffending.3

Addressing these complex issues became a priority for state leaders and served as the impetus for the task force's recommendations, which became the basis of the legislative reforms. The reforms sought to ensure that Michigan's jails were being used for their intended purpose: maintaining public safety.

The Michigan Joint Task Force on Jail and Pretrial Incarceration

Governor Gretchen Whitmer (D) created the Michigan Joint Task Force on Jail and Pretrial Incarceration in 2019, in partnership with Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey (R), House Speaker Lee Chatfield (R), Chief Justice Bridget McCormack, and county leaders, to analyze Michigan jails and draft policy recommendations to safely reduce their populations.

Task force members

Lieutenant Governor Garlin Gilchrist II (D) (task force co-chair), Office of the Governor

Chief Justice Bridget McCormack (task force co-chair), Michigan Supreme Court

Dr. Amanda Alexander, Detroit Justice Center

Honorable Thomas Boyd, 55th District Court

Sheriff Jerry Clayton (D), Washtenaw County Sheriff's Office

Craig DeRoche, faith leader, former speaker, Michigan House of Representatives

Honorable Prentis Edwards, 3rd Circuit Court

William Gutzwiller, Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police

Dale (DJ) Hilson (D), prosecutor, Muskegon County

Monica Jahner, Advocacy, Reentry, Resources, and Outreach

Dean Sheryl Kubiak, Wayne State University School of Social Work

Lieutenant Jim Miller, Allegan County Sheriff's Office

Representative Mike Mueller (R), Michigan House of Representatives

Attorney General Dana Nessel (D), Michigan Department of Attorney General

Takura Nyamfukudza, Chartier & Nyamfukudza, PLC

Commissioner Bill Peterson (R), Alpena County Commission

Senator Jim Runestad (R), Michigan Senate

Senator Sylvia Santana (D), Michigan Senate

Commissioner Jim Talen (D), Kent County Commission

Rob VerHeulen, business leader, former member, Michigan House of Representatives

Representative Tenisha Yancey (D), Michigan House of Representatives

Legislative reforms

The enacted legislation addressed four key areas: arrest alternatives, alternatives to jail sentences, community supervision reforms, and responses to traffic violations.

Arrest alternatives

Misdemeanor arrests and bookings into jail can upend people's lives and tie up law enforcement resources for what are often minor infractions. Some of this can be avoided by using citations—tickets that include a time and date for a future court appearance—as an alternative to custodial arrest for people who do not pose a threat to the community. Citations allow people charged with a low-level misdemeanor to go about their lives while they wait for their court date and enable officers to avoid the lengthy arrest process and get back on the street faster.

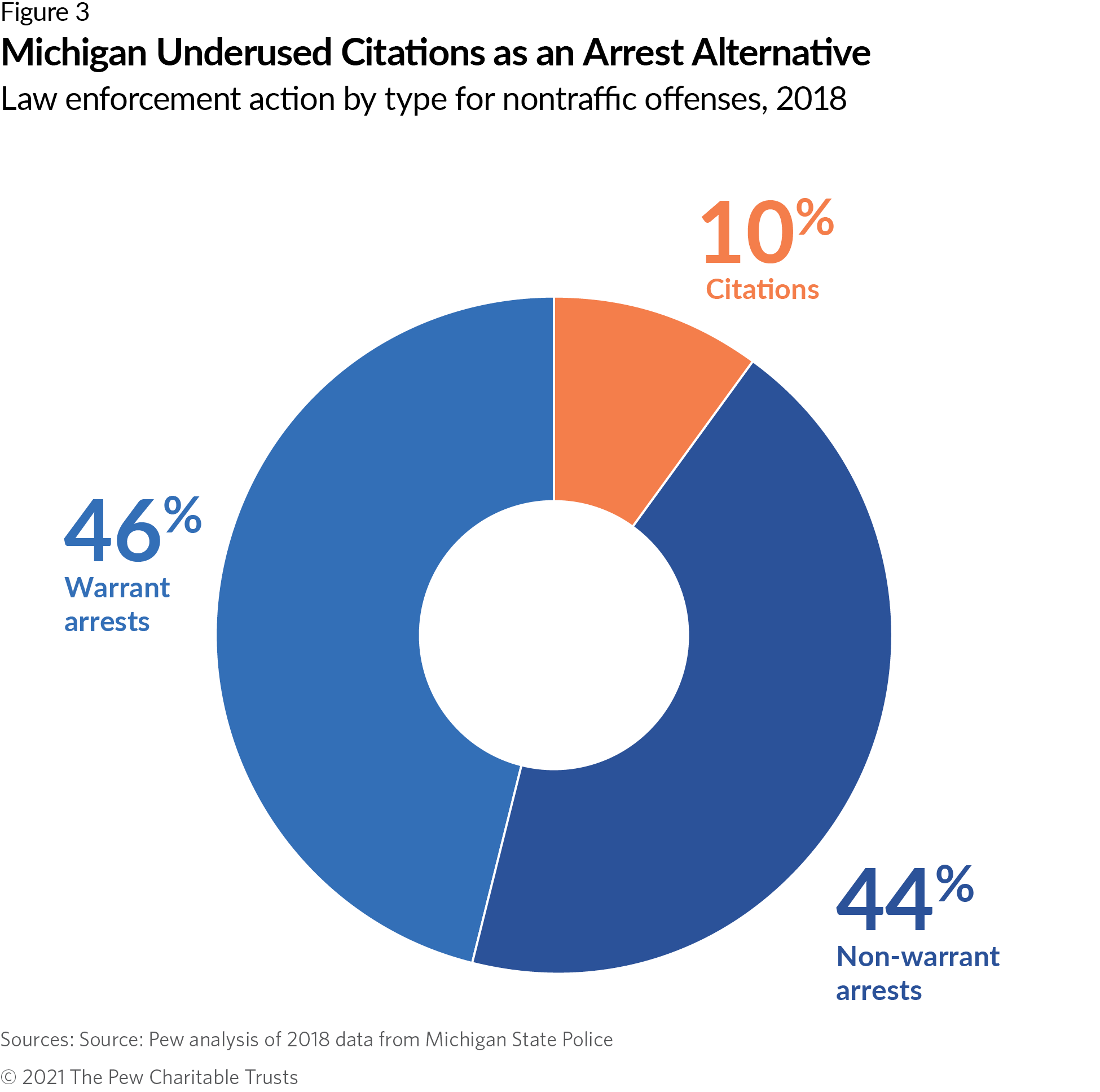

Although citations are not appropriate for all offenses, the task force found that state statute did not authorize the use of citations for many misdemeanors for which officers might want to issue them. Overall, officers issued citations in only 10% of nontraffic offense incidents. (See Figure 3.) Even for some common misdemeanors eligible for citation, such as disorderly conduct and third-degree shoplifting, officers issued citations 20% to 25% of the time, and otherwise made custodial arrests.

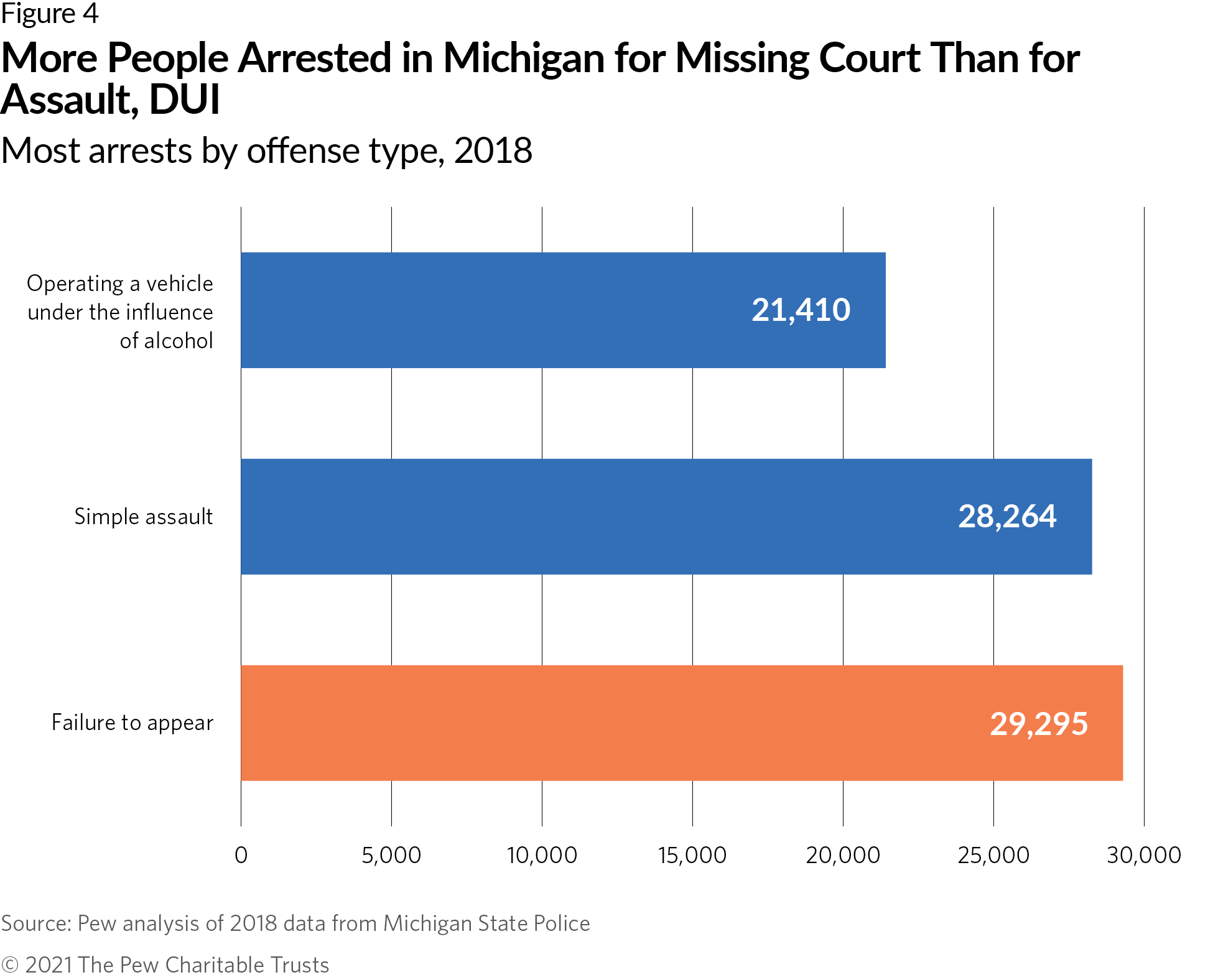

The task force also found that courts needed better options for addressing "failure to appear" charges, which stem from missed court dates and were the most common reason for arrest in Michigan in 2018. (See Figure 4.)

Most people who skip court do so not because they are trying to evade justice, but because they are unable to take time off work, do not have transportation to court, or are caring for relatives.4 Nevertheless, Michigan courts were routinely issuing arrest warrants for people who had missed their court dates, despite options to handle those situations differently.

The enacted legislation

- Expands law enforcement officers' discretion to issue citations for all but the most serious misdemeanors, getting officers back on the street faster and allowing people involved in nonviolent misdemeanors to avoid the consequences of an arrest and jail booking.

- Reduces the use of warrants to enforce court appearance by making a summons to appear in court the default method for initiating a case against people charged with nonviolent offenses and gives people who miss court for the first time two days to reschedule their appearance before a warrant is issued.

- Allows defendants with low-level warrants that are less than a year old to show up at the courthouse and be arraigned or receive a new court date without being arrested.

Relevant bills passed and their sponsors

Alternatives to jail sentences

Although most people admitted to Michigan jails stay less than a week, people serving a sentence, rather than being detained before trial, often stay the longest and take up the most space in jail. Jail sentences are costly and disruptive, and have little rehabilitative effect: Research shows that people sentenced to jail have higher recidivism rates than similar people who are not incarcerated.5

To preserve resources and limit the personal and social consequences of jail stays, the reforms prioritize nonjail sentencing for misdemeanors and low-level felonies, expand alternatives to incarceration for young people, and eliminate many mandatory minimum jail sentences.

The enacted legislation

- Requires the use of nonjail, non-probation sentencing, such as community service, behavior modification classes, or fines, as the default option when sentencing all but the most serious misdemeanors. Judges who sentence someone to jail or probation for most misdemeanors or certain nonviolent felonies must go on the record with reasonable grounds for doing so.

- Raises the maximum age of eligibility from 23 to 25 for Michigan's Holmes Youthful Trainee Act, which diverts young people from jail and allows them to resolve offenses without a criminal record.6

- Eliminates required jail time for minor offenses, including most mandatory minimum jail sentences in the vehicle code, school code, public health code, railroad code, and natural resources and environmental protection act.

Michigan has the nation's sixth-highest rate of people on community supervision.7 This means hundreds of thousands of state residents are at risk of incarceration if they cannot keep up with their probation or parole rules, such as abstaining from alcohol, abiding by a curfew, or participating in treatment programs. Technical violations—noncompliance with one or more supervision rules that may result in a sanction or revocation—are the third-most common offense for which people are in Michigan jails, another way in which low-level, nonviolent offenses drive growth in jail populations.

Michigan has the nation's sixth-highest rate of people on community supervision.

The task force found that responses to supervision violations varied widely across the state, despite evidence that providing clear, proportional responses produces better outcomes.8 Research shows that probation terms should be short and conditions should be tailored to the risks and needs of the person on supervision.

The community supervision reforms aligned with national best practices9 to conserve public safety resources and help Michigan residents succeed on supervision.

The enacted legislation

- Reduces the maximum probation term for most felonies to three years, with extensions allowed up to five years total with on-the-record justification, to ensure that people do not remain on probation longer than is necessary to complete their rehabilitative goals.

- Establishes criteria for early probation discharge—an incentive for complying with conditions of community supervision. The law requires judges to conduct a hearing before early discharge only in cases where the victim has registered to receive case updates.

- Limits jail time and arrest warrants for technical probation violations.

- Requires that probation and parole conditions be tailored to the assessed risks and needs of the person on supervision and, if applicable, the needs of the victim.

Relevant bills passed and their sponsors

Responses to traffic violations

Before the reforms, Michigan was using driver's license suspensions to penalize a variety of offenses. The task force learned that in 2018 alone, the state suspended more than 350,000 licenses for failure to pay fees or show up in court. Driving without a valid license was the third-most common reason for jail admission in the state from 2016 to 2018, but Black men and women were much more likely to be arrested and jailed for these infractions than their White counterparts (see Table 1), which significantly contributed to the overrepresentation of Black people in Michigan's jails.

Table 1

Driving Without a Valid License Was the Most Common Charge at Jail Admission for Black Residents in Michigan

Most serious charge at jail admission by race, selected counties, 2016-18

| Most serious charge at jail admission | Total | White | Black |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating a vehicle under the influence of alcohol | 14% | 18% | 9% |

| Assault | 10% | 10% | 11% |

| Driving without a valid license | 9% | 6% | 13% |

Note: Additional races are excluded from analysis because of small sample sizes; 96% of jail admissions in the counties studied involved Black or White individuals. Antrim and Muskegon counties are part of the 20-county sample of jail data collected but are excluded from this analysis because of incomplete race data.

Source: Pew analysis of sample of jail data from 20 Michigan counties, 2016-18

© 2021 The Pew Charitable Trusts

Losing a driver's license makes it hard to get and keep a job, take care of children, and run essential errands, so many people continue to drive after their licenses are suspended. And in addition to these harmful consequences, license suspension is also a major drain on the state's criminal justice resources: About half of all court filings in 2018 were traffic offenses.

After hearing from a variety of Michiganders who had been involved in the state's criminal justice system for years—or even decades—in a cycle that started with license suspension for non-dangerous driving offenses, the task force recommended that state laws change to end the practice.

The enacted legislation

- Eliminates license suspensions for failure to appear in court or pay fines and fees, except where the underlying offense is a serious motor vehicle violation, and for other nondriving crimes, such as controlled substance offenses.

- Reclassifies certain traffic misdemeanors as civil infractions, which can be handled in civil court and are not subject to arrest or incarceration.

Other recommendations and next steps

The task force put forth 18 policy recommendations. In addition to the reforms enacted in 2020, legislation addressing several additional recommendations has been introduced as part of the state's 2021-22 legislative session. The proposals in those bills primarily focus on investing in community-based treatment to divert people with mental health issues away from jails, prioritizing the needs of crime victims and survivors, and amending pretrial release policies in a way that balances public safety and liberty.

Conclusion

Michigan's historic reforms will help the state safely reduce jail populations, protect defendants' constitutional rights and ability to work and take care of their families, and reserve limited public safety resources for the people who need them most.

As jails continue to drive taxpayer costs and negatively affect the lives of residents in counties around the country, Michigan's work offers a template for states seeking to improve local criminal justice systems. By examining their county jails and offering similarly bold, data-driven proposals for change, leaders in other states can become better stewards of public safety resources and prioritize alternatives to incarceration in jail for hundreds of thousands of people each year.

Endnotes

- Michigan Joint Task Force on Jail and Pretrial Incarceration, "Report and Recommendations" (2020), https://courts.michigan.gov/News-Events/Documents/final/Jails%20Task%20Force%20Final%20Report%20and%20Recommendations.pdf. The studied counties are Allegan, Alpena, Antrim, Branch, Genesee, Gratiot, Iosco, Iron, Jackson, Kent, Macomb, Mason, Mecosta, Missaukee, Muskegon, Oakland, Oceana, Ontonagon, Tuscola, and Washtenaw.

- Ibid.

- W. Dobbie, J. Goldin, and C.S. Yang, "The Effects of Pretrial Detention on Conviction, Future Crime, and Employment: Evidence From Randomly Assigned Judges," American Economic Review 108, no. 2 (2018): 201-40, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20161503; A. Gupta, C. Hansman, and E. Frenchman, "The Heavy Costs of High Bail: Evidence From Judge Randomization," The Journal of Legal Studies 45, no. 2 (2016): 471-505, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/688907; P. Heaton, S. Mayson, and M. Stevenson, "The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pretrial Detention," Stanford Law Review 69 (2017): 711, https://www.stanfordlawreview.org/print/article/the-downstream-consequences-of-misdemeanor-pretrial-detention/; E. Leslie and N.G. Pope, "The Unintended Impact of Pretrial Detention on Case Outcomes: Evidence From New York City Arraignments," The Journal of Law and Economics 60, no. 3 (2017): 529-57, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/695285.

- B.H. Bornstein et al., "Reducing Courts' Failure-to-Appear Rate by Written Reminders," Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 19, no. 1 (2013): 70-80, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026293.

- W.D. Bales and A.R. Piquero, "Assessing the Impact of Imprisonment on Recidivism," Journal of Experimental Criminology 8, no. 1 (2012): 71-101, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-011-9139-3; J.C. Cochran, D.P. Mears, and W.D. Bales, "Assessing the Effectiveness of Correctional Sanctions," Journal of Quantitative Criminology 30, no. 2 (2014): 317-47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9205-2.

- Michigan Comp. Law §762.11, http://legislature.mi.gov/doc.aspx?mcl-762-11.

- D. Kaeble and L.E. Glaze, "Correctional Populations in the United States, 2015" (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2016), https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/correctional-populations-united-states-2015. The most recent year including Michigan data is 2015. The rate is calculated based on residents age 18 or older.

- P.K. Lattimore et al., "Outcome Findings From the Hope Demonstration Field Experiment: Is Swift, Certain, and Fair an Effective Supervision Strategy?" Criminology & Public Policy 15, no. 4 (2016): 1103-41, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1745-9133.12248/full; E.J. Wodahl, J.H. Boman, and B.E. Garland, "Responding to Probation and Parole Violations: Are Jail Sanctions More Effective Than Community-Based Graduated Sanctions?" Journal of Criminal Justice 43, no. 3 (2015): 242-50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jcrimjus.2015.04.010.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, "Policy Reforms Can Strengthen Community Supervision: A Framework to Improve Probation and Parole" (2020), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/04/policy-reforms-can-strengthen-community-supervision.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

MORE FROM PEW

Source: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2021/09/michigan-enacts-landmark-jail-reforms

0 Response to "Jails Continue to Hold in the Neighborhood of Their Capacity Quizlet"

Post a Comment